So, with another major collection of user credentials being uncovered (and reported in the mainstream media), there is a slight increase in interest in people, their data, and the credentials they use.

It’s anyone’s guess as to how long this breach will remain in the news cycle, so I thought I’d throw out an article quickly as New Zealand is currently in the throws of pre-election posturing and I imagine some political hopeful will say something controversial and the media will swing away to cover that within the next day.

For those who may not yet have caught up with the news (or those reading this in the future and wondering which massive credential theft I’m referring to), this is the uncovering of the work done by ‘Cyber Vor’ who managed to snare around 1.2 billion (yes, with a B) unique user credentials.

- “You Have Been Hacked!” – Hold Security

- Biggest Cache of Stolen Creds Ever Includes 1.2 Billion Unique Logins – Dark Reading

- Russia gang hacks 1.2 billion usernames and passwords – BBC News

- Kiwis’ data threatened after Russian hackers steal a billion passwords – NZ Herald

Credential theft is nothing new, it’s not particularly interesting news from a media standpoint, and perhaps the only reason this made the mainstream is the sheer volume which (at the time of writing) has been tipped as the largest (discovered) theft of credentials.

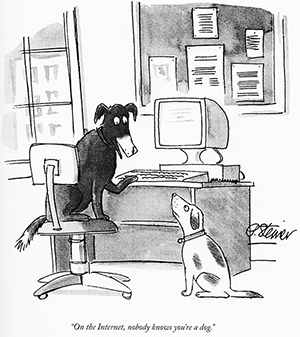

What you can do, is to think carefully about the sites that you share your information with. Remember the old adage that “On the internet, no one knows you’re a dog”, this means that if you aren’t sure about the security or longevity of the company who is seeking your information, use an alternate email address, and consider using details that may not be a completely accurate representation of who you are in real life.

I’ve written on password selection previously, and also cover passwords and credential reuse in the internet seminars I’ve presented in the past. The short version is, credentials/passwords should be:

- Strong – 15 characters or more, not a dictionary word (or string thereof), and memorable (though you can use well secured, locally stored, password managers to help with this)

- Secret – Not shared with others. While you may be cautious of where you use the credentials, those you share with may not.

- Unique – This is important and relates directly to compartmentalising your identities and credentials. If one set of username/password is compromised, your other (non-identical) credentials will remain safe.

- Changed – With each set of credentials, the impact of a breach can be minimised by changing them on a semi-regular basis. This means that, if a site is compromised, your credentials can only be used by the bad guys until you change them.

Remember that most users will only hear of credential beaches such as the one reported today when breaches are discovered, and considered newsworthy. Without both of these conditions, it is unlikely the end user will ever know that they need to change their username(s)/password(s).

So – what else can we do to stay safe(ish)?

Provide (actual) details only to websites with whom you have developed a pragmatic level of trust.

Most companies worthy of such trust will have a breach notification policy, that is – if they are compromised (and know about it), they will contact their users and take reasonable steps to stop unauthorised access and encourage their community to change credentials. In New Zealand, this is covered in part by Principle Five – Storage and security of personal information.

Keep an eye on your credentials

There are websites that collate a number of the exposed databases / credential sets, one that I have used is “Breach Alarm” who will check your email address against it’s database of compromised sources.

Keep an eye on companies who you’ve shared data with

Bear in mind that compulsory breach notification tends to apply more to healthcare, financial and government entities, whereas other companies who are not beholden to legislative requirements, will only notify if forced to (by researchers and the media breaking the story). Fortunately, security researchers tend to abide by a responsible disclosure policy, which gives the company a heads up (and a chance to resolve the issue), before they make their findings public.

The New Zealand Internet Task Force (NZITF) has an excellent consultation document on disclosure here.

Responsible disclosure reduces the chance of malicious attackers seizing upon the vulnerability notification, and harvesting the exposed data for their own nefarious purposes. “All your base are belong to us” by less bad guys if you will.

The problem is getting worse – be proactive.

These breaches happen, a lot. In fact the Identity Theft Resource Center recorded 614 breaches in 2013. Unsuprisingly, this made it the worst year on record (so far). One of the more mainstream breaches was that of Adobe who had 150 million exposed account credentials, leading to secondary breaches all over the Internet (due to identical credentials being used elsewhere). In the Adobe case, it was again the awesome work of Hold Security along with Brian Krebs who really dug into the breach.

Final words

- While the breach that is currently being reported on is significant, smaller breaches are occurring every. single. day.

- The ‘startup’ culture tends to spend more time on getting ideas to market, ramping up a userbase, and looking for seed capital or a buyout. Their focus tends to be less on data security, and there are a number of orphaned databases from failed (or no longer ‘cool’) startups out on the internet, just waiting for a malicious attacker to come along and nudge the code to make all the data fall out.

- Data theft is big business, your details are worth something to someone – protect yourself.

- Practice safe passwording and keep your credentials compartmentalised -don’t let one breach expose your accounts across the entirety of your online existence.

Be safe out there…